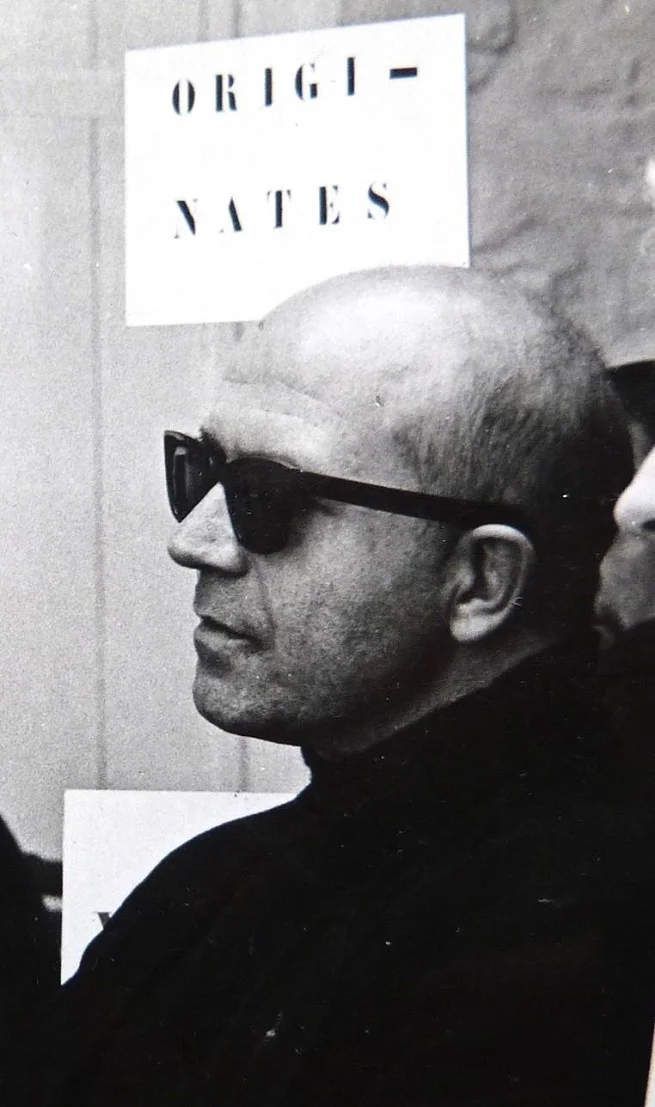

Dom Sylvester Houdard was a Benedictine Monk in Britain who was immersed in the avant-garde, beatnik art culture of the 1960s. A skilled theologian, he was on an intense quest for spiritual and contemplative awareness in his life. One of the ways he dove into his faith was by the concrete poetry art form. Concrete poetry not only focuses on the intricate combinations of words and syntax, but also on the graphical space of the words on the page. This concept harkens back to my previous post of Marshall McLuhan: The medium is the message.

The philosophy of concrete poetry is interesting to me as a technical writer and designer. Looking at the way websites, documentation, and posters are designed and structured, the emphasis on the graphical space is immensely important. You can have the best content on a website, but if it is poorly-designed, no one will want to read it. The emphasis on structure, however, invites the reader to read and comprehend the message being presented. Augusto de Capos, Haroldo de Campos, Decio Pignatari explain in Typographica that "Concrete poetry begins by being aware of graphic space as structural agent.”

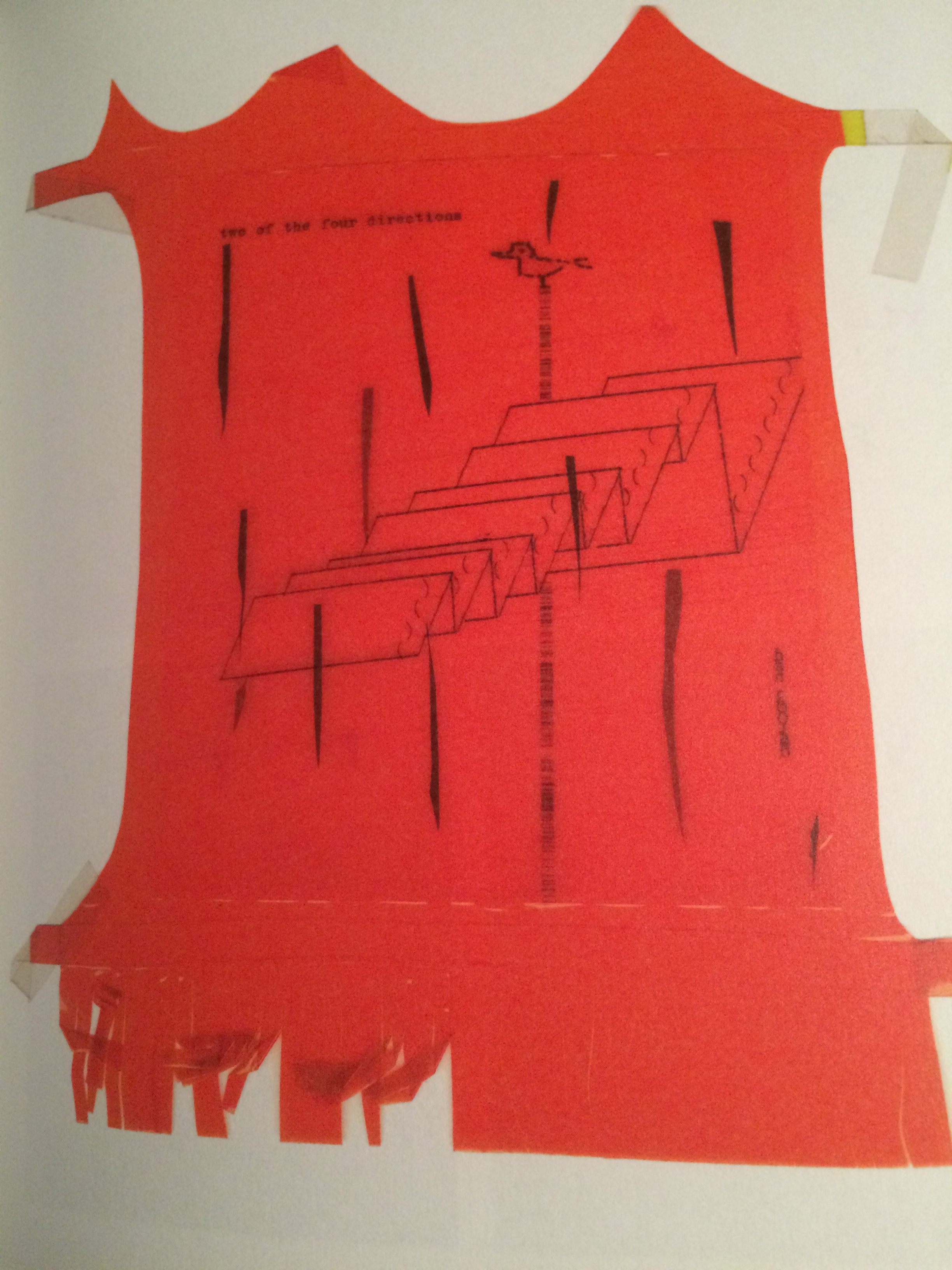

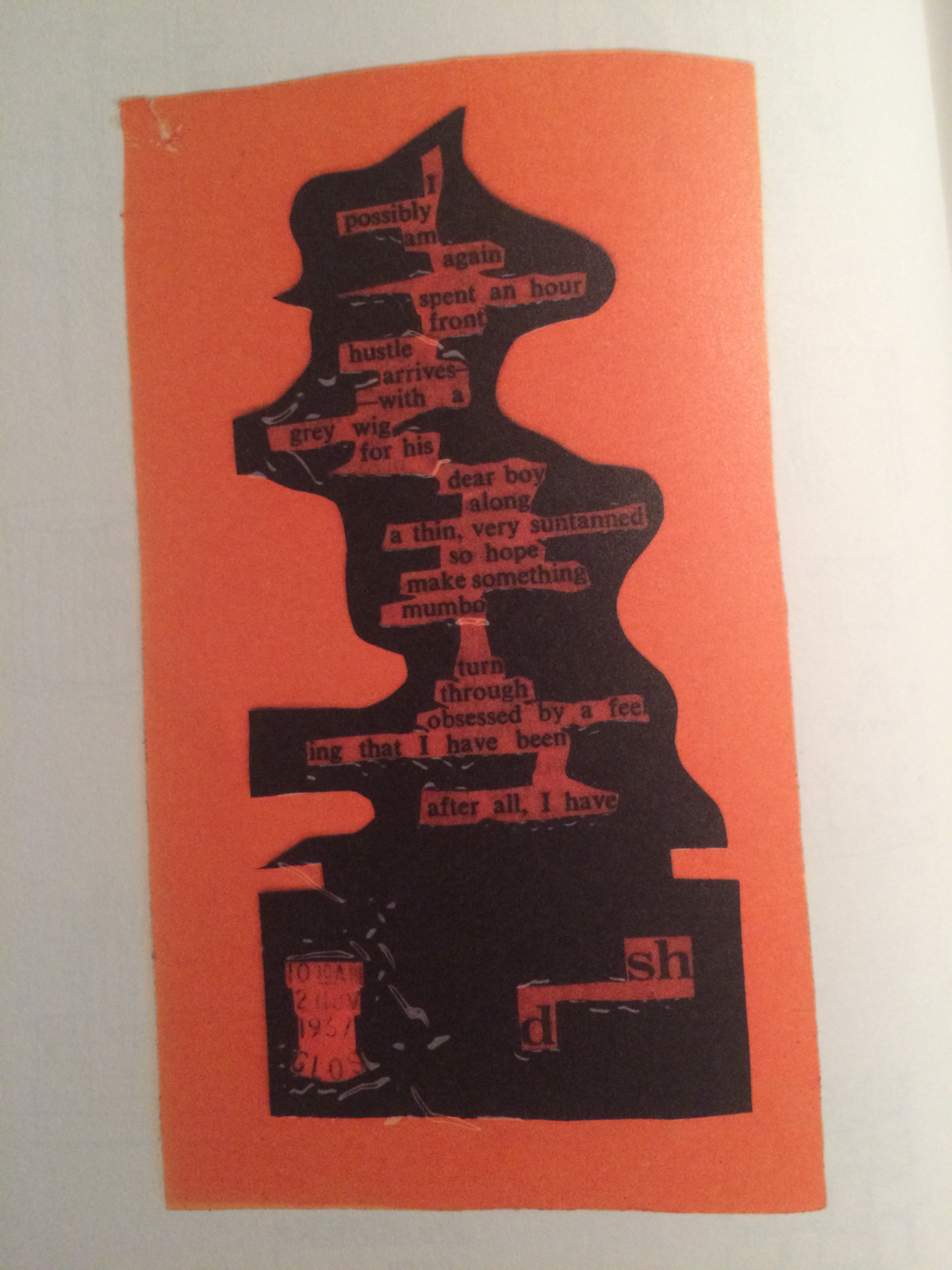

Using his Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter, Houdard created what he called, “typestracts” or, typewriter abstracts. To make these typestracts, he would use stencils and masks to create layers (similar to how we design digitally now) and turn the paper on different angles to create a dizzying effect of letters, colors, and shapes. By these strange structural contortions, the reader doesn’t really understand where to start—and maybe that’s the point. In many situations, that may be reflective to our faith life. How do we even begin to reflect on where we are spiritually?

In a sermon given at the Abbey he touches on this subject by explaining how we are ever-changing beings:

“There is only one mysterium: that is God Himself who doesn’t have being but is being: who doesn’t have life but is life and is the life he lives but never grows, never changes; who is truth and knows the truth and is his own knowledge of himself.

He alone can say I AM and he reveals himself as the one who alone is I AM: His name is therefore YAHWEH or HE IS. But though we know that God is, the meaning of the word ‘is’ we do not know: not one of us can say ‘I am’ since all we who live and grow and are conscious can say is, ‘I become, I change, I grow.”

When discussing the meaning behind his types tracts, Houdard explains,

"I see my types tracts as icons depicting sacred questions-dual space-probes of inner and outer...they should probably be viewed like cloud-tracks and tide-ripples-bracken-patterns and gull-lights-or simply as horizons and spirit-levels.”

From someone who uses abstract artwork to explain my own faith journey, I definitely relate to this concept. Sometimes, the only way to understand the meaning of everything around us to scrap organization and clean, tidy lines that are a barrier to the reality of our feelings.

If you would like more information on Dom Sylvester Houdard, check out the book, Notes from the Cosmic Typewriter: The Life and Work of Dom Sylvester Houdard.

"Almost But, Often, It Means More Than That" -January 1968.

"Two of the Four Directions" -1968

"I Possibly Am Again" -1967